Blog

Playing Valcamonica Multitouch Application Developed with Open Exhibits

In Sankt Pölten, Austria, just west of Vienna, at St. Pölten University of Applied Sciences, a Digital Media Technologies class developed a multitouch application that explores pre-historic rock art in northern Italy.

The app, Playing Valcamonica, was developed using Ideum's open source multitouch development framework Open Exhibits. Employing multitouch gestures, users of the app can explore 3.5 gigapixel images of the pre-historic rocks of Valcamonica and engage in mini-games that provide further information about the rock art and encourage interaction.

Playing Valcamonica was installed for the PITOTI exhibit at the Triennale Design Museum in Milan, Italy and was displayed from October 1 - November 4, 2012.

For more information on Playing Valcamonica see student Martin Grubinger's website.

Playing Valcamonica Promo from Georg Seidl on Vimeo.

CMME Workshop Part 1: Envisioning the Future of Accessible Digital Interactives

To launch Creating Museum Media for Everyone (CMME), a NSF grant which Jim mentioned in an earlier post, the Museum of Science, Boston held two back-to-back workshops in May 2012. Both the Possibilities and Concept Development Workshop were designed to bring together a range of experts and to make strides in developing the next generation of universally designed computer-based museum exhibits. Below is a brief recap of the first workshop and the range of ideas we heard from our expert advisors.

During the Possibilities Workshop, 46 participants from a variety of fields shared ideas and brainstormed new possibilities for inclusive digital interactives in science museums. Besides team members from the Museum of Science, WGBH’s National Center for Accessible Media (NCAM), Ideum, and Audience Viewpoints, staff from the following institutions participated: Oregon Museum of Science and Industry, The Franklin Institute, San Diego Museum of Natural History, and Balboa Park Cultural Partnership.

Over the course of the two-days, we heard presentations about the overarching goals of the project and about relevant advances in other fields of work. Participants also experimented with the latest technology available for exhibits and brainstormed ideas for digital interactives.

Our 11 expert advisors not only shared ideas from their own projects but also other useful resources. Below are brief summaries of what we learned and links to some exciting work.

Sheryl Burgstahler (University of Washington) and Gregg Vanderheiden (University of Wisconsin-Madison) both emphasized the barriers to access that still exist for many people and offered examples of the benefits of universally designed experiences. Burgstahler provided a broad historical overview of different disability models and emphasized how all experiences should be designed with usability in mind. Vanderheiden highlighted the Global Public Inclusive Infrastructures project which is exploring means for auto-personalizing people’s experiences with a variety of interfaces. Vanderheiden felt that this concept could reinvent accessibility and proposed to participants that auto-personalization would ultimately have implications for the museum setting.

Lisa Jo Rudy, Gabrielle Rappolt-Schlichtman, and Mark Barlet all talked about how museums are in unique positions to create accessible experiences. Rudy (Independent Consultant) outlined the huge variety of autism spectrum disorders and noted the strengths and challenges of the museum environment to engage people with autism in social and educational experiences. Rappolt-Schlichtmann (CAST) also highlighted how museums may risk creating exhibits that can be over-stimulating and distract from learning. By thinking carefully about the emotional experiences they are creating, she felt museums can create spaces that allow all visitors, and not just those with learning disabilities, to learn. Barlet (AbleGamers Foundation) spoke about how gaming, in particular, is one method that is underused in the museum context. He urged museums to include more accessible game-like experiences in their exhibits.

Chris Power (University of York) and Jennifer Otitgbe (Institute for Human Centered Design) presented on the importance of including feedback from people with disabilities when designing museum experiences. In his presentation, Power dispelled the myth that it was time-consuming or hard to perform evaluation with people with disabilities by explaining that talking with 7-20 participants can give one an indication of significant changes that need to be made to a product. Otitgbe emphasized how museum experiences might theoretically be accessible but in actuality are difficult for many users. She used the example that an exhibit may have captions, but only visitors will be able to tell you whether or not they are too small to be useful.

James Basham, Bruce Walker, Cary Supalo, and Harry Lang gave the final advisor presentations and each talked about specific elements of their research work. Basham (University of Kansas) highlighted his work with the Digital Backpack that provides support and technology to personalize learning. He shared his preliminary efforts to turn a field investigation guide into an iPad app that can support learning. Walker (Georgia Institute of Technology) shared insight into how sound can communicate more than music and speech. Walker provided examples of how sound can be used as a wayfinding system, can interpret dynamic exhibit experiences such as fishes’ movements at an aquarium, or can map different data points with a variety of pitches and tempos. Supalo’s (Independence Science, LLC) presentation went into detail about the development of speech-accessible laboratory probes that makes scientific lab experiences more accessible for blind and low-vision students. Lang (Rochester Institute of Technology) provided an overview of research studies about deaf education in science. In particular, he pointed out how deaf students often have low reading levels and that there is a lack of scientific and technical terms in ASL.

All of the advisor presentations provided insightful information that workshop participants referred to over the course of the week. Read the related blog post to learn more about the work that went on at the Concept Development Workshop.

CMME Workshop Part 2: Developing Innovative Accessible Digital Interactives

Building off of ideas from CMME's Possibilities Workshop, we moved into the second-half of the week and the Concept Development Workshop. This post describes what happened at this second, slightly smaller workshop and the innovative design approaches that participants created.

The Concept Development Workshop featured 40 participants working on different design teams to develop possible approaches to a universally designed digital interactive. The teams worked on one of four specified approaches they had heard about earlier in the week:

- dynamic haptic display

- data sonification

- personalization options

- multi-touch audio layers

Each team had a range of professionals including exhibit designers, exhibit developers, technical designers, evaluators, non-museum professionals, core team members, and a disability advisor. In particular, we challenged the teams to develop possible approaches for a universally designed data representation interactive exhibit --since museums frequently present data-based content and this information can be difficult for all visitors to understand.

Below are brief descriptions of what the different teams shared with each other at the end of the workshop about their work. Be sure to check-back often since the CMME team is pursuing ideas from all of these presentations and will continue to update the site with the latest news about our development process.

The group which focused on haptic displays developed a rough prototype which included a “vibrating puck.” This puck allowed visitors, through tactile feedback, to compare their data point with others and to observe trends in the data. The team explored how different levels of vibrating feedback would allow visitors to understand where their particular measurement was located and how it related to other people’s data points. Watch the video below to see a workshop participant using the dynamic haptic display prototype.

The sonification group focused on using sound to provide audio cues for visitors to be able to understand the larger trends of a data set and to be able to locate their personal data point. The prototype which they presented to the group consisted of a tactile slider overlaid on a graph. By moving the tactile slider, a visitor’s hand would travel along the x and y axis of a graph simultaneously triggering different types of pitches corresponding to data points. The team was able to use code developed by Georgia Tech's Sonification Lab to provide an auditory indication of trends within the data or where a visitor's own data point was located. Watch the video below to see team members testing the data sonification prototype.

One group at the workshop focused on personalization within exhibits and tackled the broader issue of what a personalized museum experience might look like. The group explored different variables that visitors might want to personalize at a digital interactive such as text size and contrast, audio speed and volume, and the use of image descriptions. Given the vast range of users who come to museums and their varying needs, this group developed a series of questions that museum exhibits would pose to visitors to facilitate personalization. They also considered where and how these questions would be asked to visitors. The photo below shows the team brainstorming about the series of personalization questions.

You can find information about the group that worked on adding an audio layer to a multi-touch table here in Jim’s blog post.

All of the groups made impressive headway in thinking about how each of these four approaches could be integrated into a museum exhibit that incorporates data and digital technology. The core team plans to incorporate ideas from all of the groups as it moves forward creating their various CMME deliverables, including an exemplar interactive, a DIY toolkit for other museum professionals, and papers bringing new ideas to the larger field.

Attend the HCI+ISE Conference

Human-Computer Interaction in Informal Science Education (HCI+ISE) Conference

June 11-14, 2013 Albuquerque, New Mexico

The HCI+ISE Conference, supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), will bring together museum exhibit designers and developers, learning researchers, and technology industry professionals to explore the potential impact of new human-computer interaction (HCI) technologies in informal science education (ISE) settings. The theme of the Conference is the balance between exhibit technology and the visitor experience.

The emergence of multitouch, motion-recognition, radio frequency identification (RFID), near field communication (NFC), voice recognition, augmented reality, and other technologies are already beginning to shape the visitor experience. In this three-day conference, presenters and participants will share effective practices and explore both the enormous potential, and possible pitfalls, that HCI advancements present for exhibit development.

The Conference will have activities, discussions, and group interactions exploring technical, design, and educational topics centered on HCI+ISE. A variety of technology examples such as multitouch tables, touch walls, Arduino controllers, Kinect hacks, RFID tags, and other prototypes and gear will be demonstrated.

HCI+ISE will focus on the practical considerations of implementing new HCI technologies in educational settings with an eye on the future. Along with a survey of how HCI is shaping the museum world, participants will be challenged to envision the museum experience a decade into future.

Conference events will be held in Albuquerque, New Mexico at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, and at Ideum’s Corrales studio.

Attendance at the HCI+ISE Conference is limited to 60 participants, some of whom will be invited because of their specific point of view and expertise. Conference participant interactions will provide opportunities for collaboration and potential partnerships that will persist well into the future. Applications are welcome from exhibit developers, designers, educators, researchers, evaluators, and technologists. Funding from the NSF is available to help support the travel costs of attendees. (UPDATE 2/4/2013: Applications are no longer being accepted. Applicants will be notified later this month about their status.)

The application form and More information about the Conference can be found on this website at: http://www.openexhibits.org/research/hci-ise

Conference co-chairs: Kathleen McLean of Independent Exhibitions and Jim Spadaccini of Ideum, Inc.

The HCI+ISE Conference is hosted by Ideum and Independent Exhibitions and is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1139752.

Kinect Enabled Gigapixel Viewer Part 3: Physically Using the Kinect

The Kinect is unique and extremely hygienic in the fact that it allows a user to manipulate digital items without touching anything, though arguably the part that most people enjoy more involves the part that makes them feel like they have telekinesis. This tutorial has focused on setting up the Kinect enabled Gigapixel viewer. Part 1 focused primarily on software setup and some physical space setup, Part 2 focused on using Microsoft Deep Zoom Composer to turn a high-res image into your own gigapixel image, and this section will focus on the physical setup and operation of the Kinect so you know what to expect.

There's one very important thing I want to stress about setting up the Kinect: put it on the edge of your desk/table/shelf/whatever you have it resting on.

The reason for this is you want an accurate depth picture, and you don't want the infrared beams and sensor cut off by a huge chunk of desk in the bottom of its field of view.

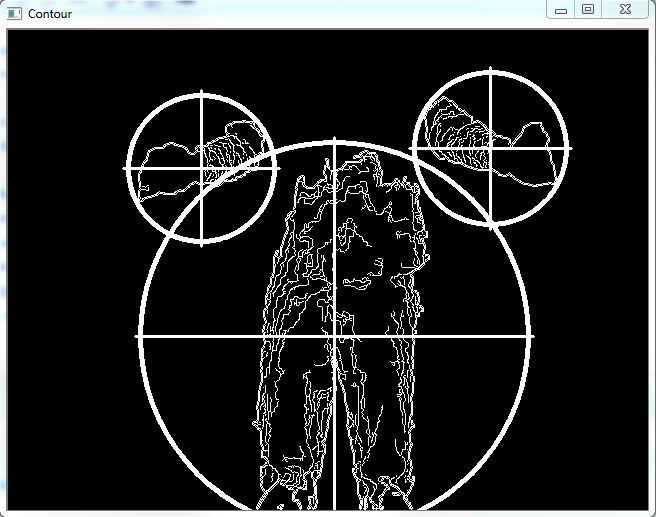

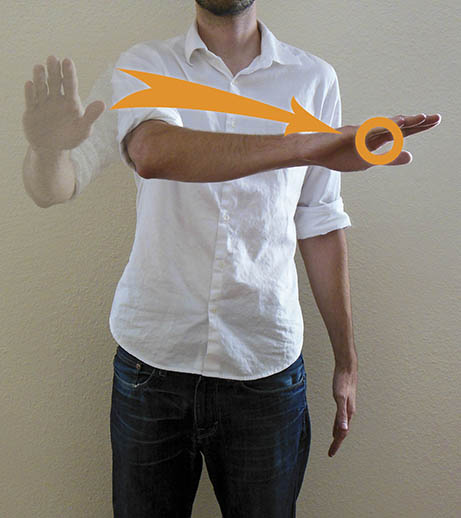

The Kinect works by broadcasting what's basically an infrared checker pattern. The placement of its sensors helps to interpret the depth, as well as the way the checker pattern warps around curved surfaces, such as a person's body. The TUIO Kinect Complete package hooks you up with a blob tracker, which looks for significant blobs and translates them into touch points in the OpenExhibits Framework. This means you can use these touch points to track drags, touches, pinches and zooms.

The TUIO Kinect Complete Contour software comes already set up, you shouldn't have to worry about adjusting or calibrating your depth, though you will probably need to experience for yourself when it starts to really track your body parts. As the TUIO Kinect Complete uses a blob tracker and not a skeletal tracker, any part of your body can become a touch point at the right distances.

For our setup here at Ideum, the ideal threshold is about six feet away. This means once a person reaches their hand within six feet, the Kinect starts registering it as a touch point. This is something to keep in mind when preparing your Kinect, it's nice to give a marker of some sort to note where this threshold of interaction is.

The next thing to remember is a user's hands, or body parts (I'm not saying you should try to control a gigapixel image with your pelvis, but if if it "somehow happens", you probably should put a video up on the internet and link it here so we know what was going on) are being tracked as touch points. This means you primarily want to imagine one-point-drag, two points to pinch and zoom.

You will also want to pay attention to your threshold of interaction. It's better to push your hand(s) in, manipulate the image, and pull them back out of range, reset your hands, and repeat. This gives you swimming and paddling motions to zoom in, or pan across. If you find the viewer becoming unresponsive, try dropping your hands down to clear your touch points, then reach back up.

And that's the end of this three-part tutorial session on how to manipulate the Gigapixel Viewer using what appears to everyone else to be Jedi mind tricks. Hopefully you've been able to get your Kinect set up, installed, and working with the Kinect Gigapixel Viewer, as well as make your own branched, gigapixel images. Or at least you know how to go about making your own gigapixel images even if you don't have any you need to make.